Ever wonder the speed of a raindrop falling? Raindrops typically fall at about 10 meters per second and if not slowed by leaves and other types of vegetation

Rain and Regenerative Management

By: Wendy Millet and Mark Biaggi

Ever wonder the speed of a raindrop falling? Raindrops typically fall at about 10 meters per second and if not slowed by leaves and other types of vegetation, will hit full force on the soil. The impact of millions of falling raindrops hitting the ground is enough to cause erosion and soil loss if plants are not present to reduce the impact of those drops. If soils are compacted, water can’t infiltrate and may pool or sheet causing the loss of both topsoil and available water to replenish underground aquifers.

Ever wonder the speed of a raindrop falling? Raindrops typically fall at about 10 meters per second and if not slowed by leaves and other types of vegetation, will hit full force on the soil. The impact of millions of falling raindrops hitting the ground is enough to cause erosion and soil loss if plants are not present to reduce the impact of those drops. If soils are compacted, water can’t infiltrate and may pool or sheet causing the loss of both topsoil and available water to replenish underground aquifers.

In the work we do raising food and caring for land, water is a frequent topic of conversation. Whether we are discussing that there is not enough, too much, or when it will come our way, water comes up multiple times a day! Because water plays such a pivotal role in everything we do and is the primary limiting factor for rangeland productivity, we thought we would share a little bit about how we think and talk about water at TomKat Ranch.

As we work to regeneratively manage rangelands, important questions we ask ourselves about water include:

- How can we protect our soils from surpluses or deficits of water?

- How can we regeneratively manage the land so that every drop of water that falls has the best possible impact on the ecosystem?

TomKat Ranch is located in Central Coastal California and experiences a Mediterranean climate characterized by cool wet winters and mostly dry summers, with the typical rainy season occurring from November to May. Climate projections for the area indicate that temperatures will continue to rise, making droughts more likely and winter storms more intense.

Given this, managing land so it can thrive during drought, changing temperatures, and even intense storms is a key focus of our land management. To do that, actions that promote effective rainfall – that ensure rain is actually absorbed and usable by the ecosystem, are key. Effective rainfall can be improved by keeping the soil covered to protect it from erosion and promoting soil conditions such that the rain soaks (infiltrates) into the ground and can be retained by healthy soil. With our mission to demonstrate and broadcast the benefits of regenerative agriculture, we also monitor and share the results we see.

Rainfall rates at TKR for the last 6 years (as of January 1).

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

| 12.26” | 4.05” | 6.7” | 9.38” | 3.41” | 20.60” |

As of January 1st, 2022, TomKat Ranch has received nearly 21” of rainfall in the 2021-2022 wet season. A particularly stormy October (2021) accounted for 8.55″ of rain, very nearly half the total rainfall received thus far and more total rainfall than we got in 3 of the 4 previous rainy seasons. The October rains were followed by particularly warm weather, and this sequence of wet weather and warm temperatures created phenomenal grass-growing conditions. Even though the rains were intense, the high density of plants growing in and covering the soil meant that water infiltration rates were high and the land will continue to benefit.

Last week, we took a walk to a couple of spots on the ranch to look at the results of our regenerative management in the context of this very intense early rain. Here is what we saw:

1st Observation: Goat Grazing

We looked at a hill where we adaptively grazed goats in May of 2021 to promote plant diversity and reduce fuel loads and wildfire risk. Previously, this hill had been choked by poison oak, briar, hemlock, and coyote brush. This coastal scrub provided some cover to the soil but also prevented grasses and forbs from growing and left a lot of soil bare. Looking at the impacts of grazing less than a year later, the hill has been transformed into a highly diverse area of grasses, forbs, and even a few legumes. There is still some poison oak, hemlock, briars, and coyote bush, but they no longer dominate the area. A healthy understory of grasses and forbs is now covering and protecting the soil, dramatically improving the field’s ability to soak up rain and reducing fire risk. The goats’ browsing and trampling woody fuels to feed themselves and the soil microbes was a much better use of these plants!

Previously, this hill was choked by poison oak, briar, hemlock, and coyote brush. While providing some cover, these plants prevented grasses and forbs from growing, leaving much of the soil bare. Less than a year later, the hill has been transformed into a highly diverse area of grasses, forbs, and even a few legumes.

2nd Observation: Cattle Grazing

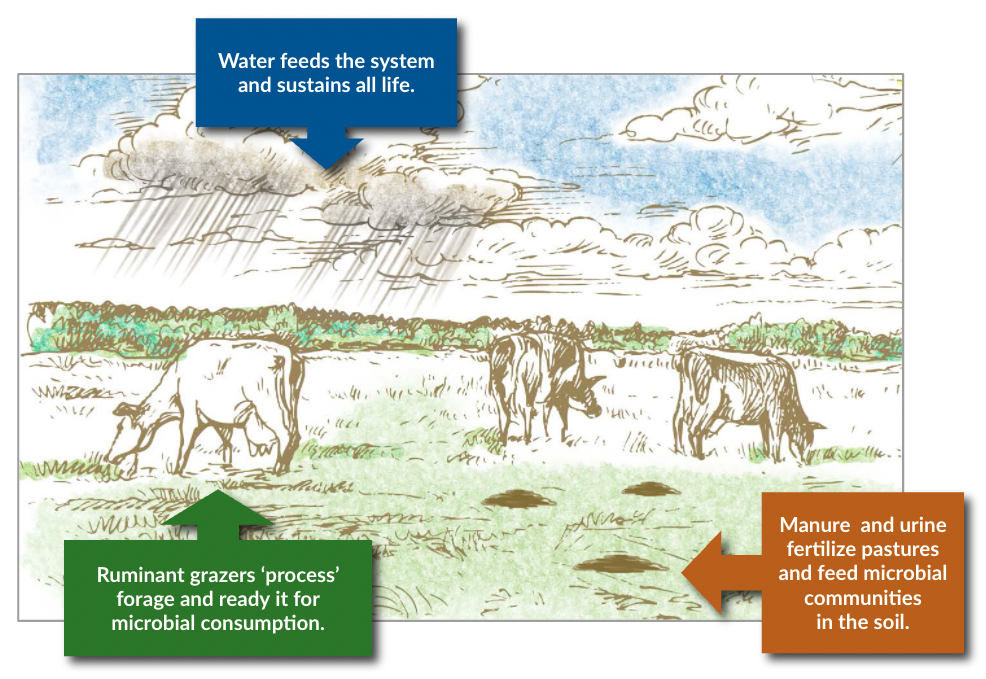

We looked at a pasture where our herd of adaptively managed grass-fed cattle had recently grazed (cattle are typically moved daily). It was great to see high plant diversity and little bare soil. Meanwhile, areas that had been previously grazed had sufficient ground cover to both protect the soil and allow plants access to light for regrowth. Healthy manure pats from the cows littered the field; their consistency evidence that the available forage matched the “forage” needs of the microbes residing in the cattle’s rumen and evidence of the cycle of life–from soil to forage to grazer and back–as digested grass and microbes in the manure become food for future soil microbes and other species.

The cycle of life from soil to forage to grazer and back as digested grass and microbes in the manure become food for future soil microbes and other species.

Given the volume of rain that had recently fallen, it was no surprise that water was bubbling up out of the ground in some places. There were also areas where the cattle had concentrated at a fence corner and churned a path with their hooves. While we would prefer not to create such impacts for both ecological and aesthetic reasons, they are a natural result of grazing herds in the rainy season (similar to the wildebeest of Africa or the American Bison of centuries past). Based on experience, we have seen that as long as we allow the land to recover and regrow after such disturbances, the mud and trampling are short-term impacts on forage productivity.

Continuing to Learn

Water is an absolutely crucial part of all working and natural lands. Learning how to manage it in a way that promotes healthy water cycles is integral to regenerative management. In addition to continuing to trial, experiment, and collect observations, we also monitor the following water parameters:

- Steam Flow, Stage, and Temperature: Our partners at Point Blue Conservation Science help us monitor the health of Honsinger Creek (a small creek that runs through the center of ranch) including flow, stage, and temperature. Over the years we’ve seen that management actions like restoring riparian areas and promoting upland soil carbon sequestration are ways we can improve the health of the riparian and aquatic systems.

- Water Quality Monitoring: Each year we conduct water quality tests in Honsigner Creek following the “First Flush” protocols of our local San Mateo County Resource Conservation District (RCD). This effort tracks pathogens, nitrates, and heavy metals in the water. Monitoring results each year helps us better understand the impact of our management practices.

- Fish Counts with CalTrout: Water is critical for all life and crucial habitat for salmonids and other aquatic species. Thanks to CalTrout, the health and diversity of fish populations are monitored annually in Honsinger Creek (80% of this creek’s watershed is on the ranch).

- Soil Water Infiltration: As part of our participation in Point Blue Conservation Science’s Rangeland Monitoring Network, we conduct standardized soil health monitoring at 40 sites across the ranch, including soil water infiltration, bulk density, and soil organic carbon.

We hope this brief article about our work will help you think more holistically about water. For more information about managing water on rangelands, we’ve been particularly inspired by the following:

- Water in Plain Sight: Hope for a Thirsty World – Judith D. Schwartz

- Regenerative Rain Making – Understanding Ag

- USDA Rainfall Simulator

- White Oak Pasture- Water Cycle Demonstration

In addition, in a recent webinar in an agriculture-focused series hosted by Business Climate Leaders, Dr. Carolyn Olson, one of the coordinating lead authors of the Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4), shared many valuable resources for identifying and managing the impacts of climate change, such as changes in rainfall and temperature, on agriculture. For a regional, state-by-state review of the study’s findings, see National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) recently published State Climate Summaries.

Copyright © 2001 – 2021

TomKat Ranch | +1 650-879-0779

reachout@tomkatranch.org | webmaster